Basic Concepts

Molecules exert forces on each other, and to simulate the behavior of a large collection of molecules it is necessary to have some rule or formula that quantifies these interactions. A convenient way to represent the forces is via a potential-energy function, a.k.a. the intermolecular potential. Such a model needs to be reasonably simple so that many molecules can be simulated for useful time intervals without requiring an excessive amount of computation. The Lennard-Jones model is a very popular choice, not so much because it is a very good model, but more because it has been used so much in the past, and much is known about it already (plus it is not altogether bad). The Lennard-Jones formula for the potential u is

where r is the distance between the centers of the pair of atoms, and and are potential parameters that characterize the size and strength of the potential. The potential energy of a collection of N atoms is given by the sum of the Lennard-Jones potential applied to each pair; models of this sort are called pairwise additive. The Lennard-Jones potential is spherically symmetric---it depends only on the distance between the pair of atoms, and not their relative orientation. It is depicted here

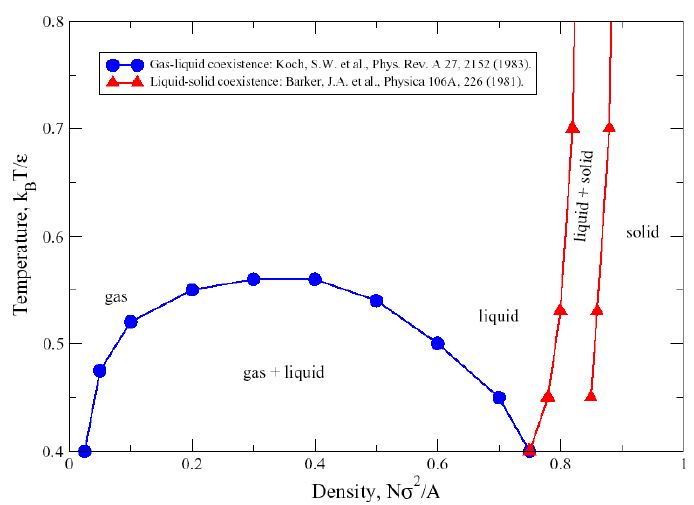

The energy grows very large for separations less than one diameter , and there is a well of attraction of depth just beyond the repulsive region. Mechanical systems tend toward lowest energy, so a pair of atoms exert forces on each other that try to drive them to the separations corresponding to the bottom of the well. Of course, it is geometrically impossible for every pair of atoms to be at separations corresponding to the minimum energy. Moreover, thermal energy (manifested as collisions between atoms) constantly knock atoms pairs away from (or toward) the minimum-energy separation, and the overall behavior of the collection of atoms can be quite complex. Still, simple but meaningful measures of behavior can be defined and observed, and this module permits examination of some of the most important such measures.

When studying the Lennard-Jones model it is convenient to express its properties in units such that the diameter and well depth are both unity (1.0). Dimensioned quantities, such as the energy u and the separation r as shown in the figure, are expressed as dimensionless groups formed with appropriate combinations of and . The pressure is made dimensionless this way by forming the group (where d is the spatial dimension). To recover the actual pressure given a value in dimensionless form, one needs to select (dimensioned) values of and appropriate to the substance being modeled, and then multiply/divide through to recover the dimensioned value of the pressure.

Quantities involving time require an additional fundamental unit to be made dimensionless. A convenient choice is the mass m of the atom. A dimensionless time can then be formed from the dimensioned time t as .